Nyam Nyam \ Biography

Trevor Simpson: I'd known Paul since we were four, at Primary School. When we were 15 I started playing drums. I remember rehearsing in my front room with Paul, and Nick Hunter coming round with a bass he couldn't play. But he also brought Raw Power - the first time I heard it. Obviously Paul chose Grant Ardis over me on drums because he could actually play. Then I think Mental Block split up, we kept in touch and used to meet at the Welly Club.

Paul Trynka: I'd formed Mental Block, Hull's first punk band, with Nick Hunter - we started in 1976, and used to phone up and gossip with Malcom McLaren and Lee Childers. But it was nearly all covers. Trevor had been trying the bass, and we started working on songs together. The first public gig as Nyam Nyam was at the Wellington Club, December 13th, 1979.

Trevor: Our drummer, Dave Jones, was slightly older than us and hung out at the Welly. He was into Jean-Paul Sartre; he was leafing through Nausea, we said we'd point to a word and that would be the name of the band. He pointed - and there was Nyam Nyam, an African tribe. We said we'd go with that name for now.

Paul: Dave learned drums from scratch, more or less. He was great, very specific about what sounded right and what didn't.

Trevor: Dave and I would rehearse in his garage trying to come up with a sound. I was listening to a lot of music, Pere Ubu, Final Solution, where the bass had a more dominant role.

Paul: Knowledge was the first song that really worked. That was our contribution to Mrs Wilsons' Children, a Hull compilation, released March 1981. It was the start of a beautiful time when you'd be listening to John Peel and your own record would come on, maybe with a couple of words of approval, little moments that felt life-changing.

Trevor: We played the Welly a lot, lots of Rock Against Racism gigs and shows on the East Coast. Including one at Hornsea Floral Hall. No wonder Dave never played with us again.

Paul: The Floral Hall had a raked wooden stage. We'd start with this bass and drums build-up, then I'd run to the mic, hit the opening chords and start singing. Except for this gig, when my trendy Chelsea boots skidded, I smacked into the mike and split my lip while the kids in the front row fell over laughing. Meanwhile, Dave's kit was constantly sliding away. In the stress, he simply forgot how to play the drums. He left, insisting he was no good, despite our entreaties. I had to play drums on our demos for a bit.

Tim Allison: I worked with Paul at Beverley Music Centre and he had this rough demo of Laughter. I sat down and came up with this organ part. It just seemed to fit. Jock, our new drummer, came at more or less same time, he was quite young and made it clear he wanted to drum 'till September but was then off to University.

Trevor: Jock added quite a lot to Laughter, he was really good at working with stuff that was more arranged. And he played on Knowledge (Chapter 2).

Paul: We made Laughter because someone wanted it on a compilation, then we decided to do it as a single. We discovered a great studio, Cargo, for the B-Side. Meanwhile Trevor had started this correspondence with 4AD.

Trevor: A friend's brother told us he was working at 4AD. He'd also told me you paid £20 for a haircut in London. I sent him a copy of Laughter and a letter saying, You must be making a fortune if you're spending that much on your hair. Weeks later I got a letter back from Ivo Watts-Russell, head of 4AD, saying "I've never heard of this man!" But he liked the single, said, It's not really right for me but I'll pass it on. Then Vaughan Oliver [4AD graphic designer] was really into it. We loved his sleeves too, so I kept writing to him.

Vaughan Oliver: I do remember being a big fan and advocate. I used to enthuse about it whole-heartedly. It was probably something I was promoting for 4AD but it didn't happen. This was early on in 4AD, so maybe Ivo did have more of a distinct vision.

Paul: I'd sent a single to John Brierley at Cargo in September 1981. New Order were in, working, Peter Hook saw the sleeve, liked the music, then wrote to me, offering to help however he could. What a mensch he was. Meanwhile, we'd found Steve Jessop to play drums. The first tryout he really made sense of Hope Of Heaven, playing rimshots; it was starker, simpler.

Steve Jessop: I remember screwing up the first rehearsal and thinking, "This isn't the jangly pop I'm used to." I got hold of a great kit, a Gretsch, from a guy needed the money to buy a new pigeon loft.

Tim: We'd made a demo of Fate. I'd been listening to a lot of electro, and we did a new version with a sequencer.

Peter Hook: John used to pin all the singles up on the wall. I listened to them all, in the downtime. There was you, and another group I picked, The Singles, 'cos the title of their song was Adolf Hitler, who were interesting. I was always very receptive then, like the Happy Mondays gave me their tape. I used to acquire it all.

Paul: We'd sent demos to Aura, who had Nico and Annette Peacock, and they offered us a deal for Fate. Hooky said he'd produce it, and would check over the contract. Then he said, "Why don't you put it out on Factory Benelux?" Which is what happened.

Peter Hook: For New Order it was a very interesting period, you were completely workaholic, all four of us were. In an odd way, you weren't going enough with New Order, so you were happy to do more. It was an odd thing. And being in a group is all about compromise - and as a producer you get to enjoy yourself, to be the lord of the manor.

Tim: It was brilliant. This was at Strawberry in Stockport. Paul and Trevor were more level-headed, I was, Oh My God. I remember Hooky turning up and wanting the van emptied - he had all of New Order's gear and I was carrying the Emulator in, I was, Oh God, what if I drop it, they cost around 15 grand!

Paul: Hooky arrived with the TR808 programmed, plus the Blue Monday Oberheim drum machine and their Prophet 5. He suggested a new bass part and extended the song to around eight minutes, while telling us all about working with Arthur Baker.

Hooky: You seemed like very nice boys. Middle class. The keyboard player seemed posh. It was an absolute pleasure to work with you. You listen now and it's so long, but in those days that was the fashion, the 12 inch version.

Steve Jessop: It was weird. But it was great. He did knit it together like a jigsaw, while he was probably learning about producing.

Tim: The first night we slept in the van. I remember going out with Steve to find a swimming pool to freshen up, then Hooky took us in on the second night. We slept on his floor and he made bacon sandwiches for breakfast. I used his toothbrush. A good, genuine, generous person.

Paul: Fate/Hate wasn't how we'd do it - but that was what was good about it. It reached several dance charts, probably down to the New Order connection. Then of course, when Beggars Banquet, who owned 4AD, heard we were making this single, having dithered for ages, they suddenly decided to sign us for the album. The recording advance was low - much later, Hooky said, Well, Factory Benelux would have given you more. We were, What, you wanted an album, why didn't you say?

Trevor: The songs I enjoyed playing most were The Illuminated Ones... the way the song constantly changes. And Hope Of Heaven. Out of all the songs we do it's the closest to what we were trying to achieve. When you find your natural place. And the best version is the one on the demo... We couldn't get the rimshots right when we recorded the album at Fairview.

Paul: I feel lucky we got to record those songs, because the best ones - Hope Of Heaven, The Meeting, And To Hold, The House, and later The Architect - were about people I knew, or met. Casualties. Hull could be an extreme town. The Meeting was about a friend who had been gang-raped; what can you say when you hear that story? The House was an acquaintance, who'd killed himself. And To Hold was about a local man who'd murdered his wife, called the police and told them not to wake his kids when they came for him. In that atmosphere... I often thought I'd lose my mind. Those songs helped exorcise those feelings. I often think back to those people and hope they pieced something together out of their lives.

Vaughan: I remember researching photographs that seemed appropriate for the cover. The girl over the shoulder was one of my favourites of Nigel's and you guys just took to it. There's a beautiful melancholy in your work that comes across startlingly in that image.

Steve: Hooky came over with his Megatron keyboard for the session... That was quite good.

Paul: New Order were recording Low Life in the daytime, so Hooky left in his Audi Quattro at midnight, crossed the Pennines in about 45 minutes, with their Emulator and Prophet 5 so we could overdub all the keyboards in one night. Then he drove back to work on his own album.

Hooky: I enjoyed listening to it a lot. But it was very, very melancholy and quite... poignant. More Velvet Underground than Fate/Hate was. I couldn't imagine you playing them live - they were quite soft. They were quite shocking, some of the lyrics.

Trevor: It was all night sessions, because that was cheaper. You'd get home and even though you'd been at it all night first thing I did was put the tape on, then go to work. Some of it was hard - that typical '80s thing of spending ages on the drum sound so your fingers would be sore before you'd played anything. But we did really get into it.

Paul: A friend, a great musician called Paul Moller, played violin and sax. He'd wait for me to finish a really emotional vocal take at four in the morning, I'd walk out into an dark, empty studio then he'd leap out and honk the sax right in my face, freaking me out. Then at five in the morning, we'd push my girlfriend Sarah's Morris Marina off in the snow to start it - I had to get it back at six so she could get to work on a local pig farm.

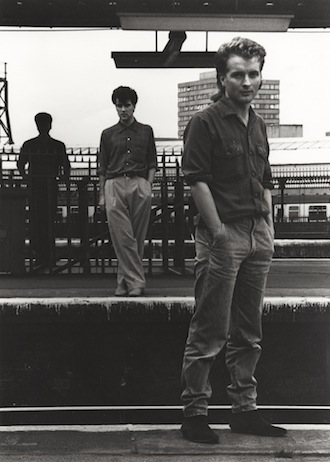

Trevor: For the first time, we were developing as a band and had reached a peak with Hope of Heaven and The Architect. We were playing places like Stockton on Tees, a venue that had a piano, so we could do two sets, a quiet set and an electric set, where we could stretch out more. Not a rock band, not a dance band.

Paul: The ICA Rock Week, where we headlined with The Triffids, was amazing - we'd done support slots to Modern English, and smaller dates, endless trips down the M1 - we got reviews saying things like "this will go down in history". But then it was back to Hull with nothing to do. Not enough shows.

Steve: Maybe the album could have sounded better. But it sounds great to me. From when I first heard the band, a lot of people thought it was depressing - but I always found it uplifting. But we were just naÔve. We didn't have the knowledge of how to do it or the confidence.

Paul: The press response was great - of course it's hilarious, in retrospect, to be labelled a "Great White Hope" and then sell zilch! But after we moved to Beggars, John Walters decided he didn't like us, so there was no more from John Peel. Then Beggars wanted Robin Guthrie to produce us. We loved the Cocteaus but we didn't want to sound like them. Finally Beggars agreed to pay for The Architect EP at Palladium in Edinburgh. Palladium had a proper piano... which is important to piano-based songs. This was a belated realisation.

Trevor: Scotland was beautiful, a relaxed, good studio with a good sound. I played slide for the first time, there was Moller's influence with the sax, and there was Ronnie Rae who played bass - did a perfect job on a song he'd only heard 10 minutes before.

Paul: The Architect was from an overheard conversation. A girl talking to an older woman, I think, on a station platform. She'd been beaten up by a pair of squaddies. She didn't know yet if she'd be scarred for life, or not.

Vaughan: The Architect had a buff cover, a different shade to the album. It had textured, distressed lettering I was working on, that everyone opted into a few years later as downloaded fonts. That lettering was created specially for Nyam Nyam on the old PMT machine. I think that photo was the This Mortal Coil girl. Why a girl again? Well, there's a strong femininity in the music - it's not bridling with machismo, is it? There's a gentleness there, a sadness and melancholy.

Paul: Vaughan Oliver had been our biggest supporter at Beggars, along with Ivo. But we weren't signed to Ivo's label. Also they were beating their head against a brick wall trying to get airplay. I don't think Beggars ever really said they were dropping us - but our A&R left and the new one didn't return our calls. So we got the hint.

Trevor: Looking back, of course we should have pushed ourselves more. But I'm still proud of what we did.

Hooky: That's life. And then you die.

Paul: We all moved on. I moved to London, so did Steve, Trevor went on to play in What Katie Did Next, with Paul Moller. I see Trevor pretty often, and we'd often say we'd have to work on a song properly. So it was very moving to do one, using the excuse of this LTM reissue. Very surreal, back with Trevor and Grant on drums, who lives near him and was in my very first band.

Trevor: Why did we split up? You didn't tell me we'd split up! I thought we were on a break!

Some extended interviews from these notes are at nyamnyam.co.uk

![COOL AS ICE: BE MUSIC PRODUCTIONS [LTMCD 2377]](../images/ltmcd2377.jpg)

![FACTORY BENELUX [LTMCD 2521]](../images/ltmcd2521.jpg)

![TOBACCO PERFECTO [LTMCD 2578]](../images/ltmcd2578.jpg)